Sometime in the 1850s, Bertha Wehnert-Beckmann, by all accounts the world’s first important professional photographer and definitely the first female one, had an unusual visitor in her Leipzig studio. Likely, Wehnert-Beckmann had heard of the man who now stood before her, slightly unkempt, his hair windswept, and clearly ill at ease. She might have even read his two bestselling novels about the American West, Die Regulatoren in Arkansas (1846) and Die Flußpiraten des Mississippi (1847). If so, she would have liked the almost photographic precision with which he had documented life on the American frontier.

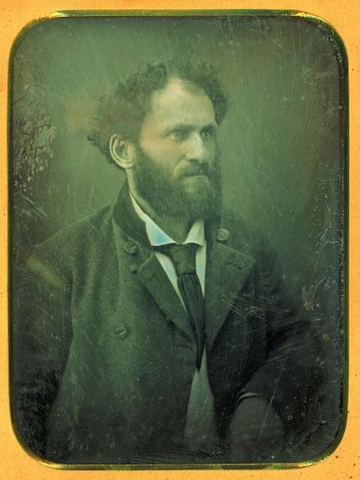

Regardless, when Friedrich Gerstäcker showed up on her doorstep, she knew she had her work cut out for her. The finished daguerreotype, now in the collections of the Stadtmuseum Leipzig, reveals why she was such a sought-after portraitist. By asking Gerstäcker turn to the left, looking at some undefined object off the camera, she not only made his thinning curly hair appear fuller than it seems in most other images, she also lessened the effect of his haunting, almost crazed stare, hard to bear for the viewer who has to meet it upfront. The pose lends respectability and weight to Gerstäcker’s appearance. It helped matters that he was dressed relatively neatly, wearing a kind of hunting coat and a tie, tucked elegantly into a light-colored vest.

As portraits go, this was a fairly standard image. What is not so standard are the two people involved, the eccentric sitter as well as his similarly unconventional photographer. Born in Cottbus, Germany, in 1815, Bertha Beckmann learned her trade in Prague. In 1845, she married the Leipzig photographer Eduard Wehnert, who died only two years later, leaving Wehnert-Beckmann to run her husband’s studio by herself. For reasons that remain unclear, she emigrated to New York in 1849, opening studios at 62 White Street and later at 385 Broadway. In 1851—again, nobody knows why—she closed her shop and returned to her previous haunts at Burgstrasse 8 in Leipzig, where she continued to work until she was in her later sixties. A staggering number of images (over 4,000) can be attributed to her, among them the first known erotic photograph, a double portrait of two partially clad young women, one reclining on a chaise longue, the other cowering in front her—separate yet, the viewer is supposed to believe, united in their dreams. Surviving pictures of Wehnert-Beckmann shows an energetic woman who wore her hair neatly parted in the middle, her steady, keen gaze matched by her stiff, slightly forward-leaning posture—a far cry from Gerstäcker, who always looked a little rumpled, as if he had just been chased by a bear. But what the world’s first photographer and the author of the first German western had in common was a shared experience of temporary emigration to the United States—a handy topic of conversation, one assumes, as Wehnert-Beckmann was trying to get the usually fidgety writer to sit still for his portrait. Neither of them had been casual visitors to the New World. Gerstäcker had worked as farmer, silversmith, hotelkeeper, hunter, and trapper while sending home copious notes about his experiences; Wehnert-Beckmann had built a hugely successful photographic business, whose long list of clients included Senators Henry Clay and Sam Houston as well Millard Fillmore, the 13th president of the United States.

But Wehnert-Beckmann’s and Gerstäcker’s portraits also point to something else, less tangible that they shared—the same mix of unflappable, fierce determination and crazy passion that no doubt helped them produce more work than most of their contemporaries. (Gerstäcker’s complete literary output would eventually comprise 44 volumes, no mean feat given that he lived to be only fifty-six.) Anglophone readers will now get a fresh chance to sample the barely subdued wildness so ably captured in Wehnert-Beckmann’s daguerreotype. For the first time, one of Friedrich Gerstäcker’s most popular novels, Die Regulatoren in Arkansas or The Arkansas Regulators, will be available in a complete English translation, undertaken jointly by Charles Adams and me (available from Berghahn Books in January 2019).